1. Introduction

Renewable energy sources play a pivotal role in addressing the global energy crisis. Unlike fossil fuels, which deplete over time and contribute to environmental degradation, renewable energy harnesses naturally replenished resources. The transition towards sustainable energy is essential for mitigating climate change, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and ensuring long-term energy security.

1.1 What Makes Geothermal Energy Unique?

Geothermal energy stands apart from other renewable sources due to its reliability and continuous availability. Unlike solar and wind energy, which are intermittent and weather-dependent, geothermal energy provides a consistent and uninterrupted power supply. Its origins lie deep within the Earth, making it an abundant yet underutilized energy resource.

1.2 The Growing Need for Sustainable Energy Solutions

With the rise in global energy demand and increasing concerns over carbon footprints, the necessity for sustainable alternatives has never been greater. Geothermal energy, with its low environmental impact and vast potential, offers an effective solution to reduce dependence on fossil fuels while ensuring energy stability.

2. The Science Behind Geothermal Energy

2.1 The Earth’s Internal Heat

The Earth continuously generates heat from radioactive decay and residual primordial energy from planetary formation. This immense heat reservoir is harnessed for various applications, from electricity generation to direct-use heating.

2.2 How Geothermal Energy is Generated

Geothermal energy is extracted from the Earth’s heat reservoirs through wells and heat exchangers. This energy is then converted into electricity or utilized for direct applications such as district heating and industrial processes.

2.3 The Role of the Earth’s Crust, Mantle, and Core

The Earth’s structure consists of the crust, mantle, and core, each contributing to geothermal heat distribution. The outer crust contains accessible geothermal reservoirs, while the deeper mantle and core store vast amounts of heat, presenting future opportunities for enhanced geothermal systems (EGS).

2.4 The Geothermal Gradient: Why Heat Increases with Depth

The geothermal gradient refers to the rate at which temperature increases with depth in the Earth’s interior. On average, temperatures rise by 25–30°C per kilometer of depth, although this gradient varies based on geological conditions, influencing the feasibility of geothermal energy extraction.

3. Types of Geothermal Energy Resources

3.1 Hydrothermal Reservoirs

Hydrothermal reservoirs contain naturally occurring hot water and steam trapped in porous rock formations. These reservoirs are the most commercially viable geothermal resources and are commonly used in power generation and direct heating applications.

3.2 Hot Dry Rock Systems

Hot dry rock (HDR) systems lack natural water content but contain significant geothermal energy potential. By injecting water into deep fractured rock formations, heat is extracted and converted into usable energy, expanding the scope of geothermal utilization.

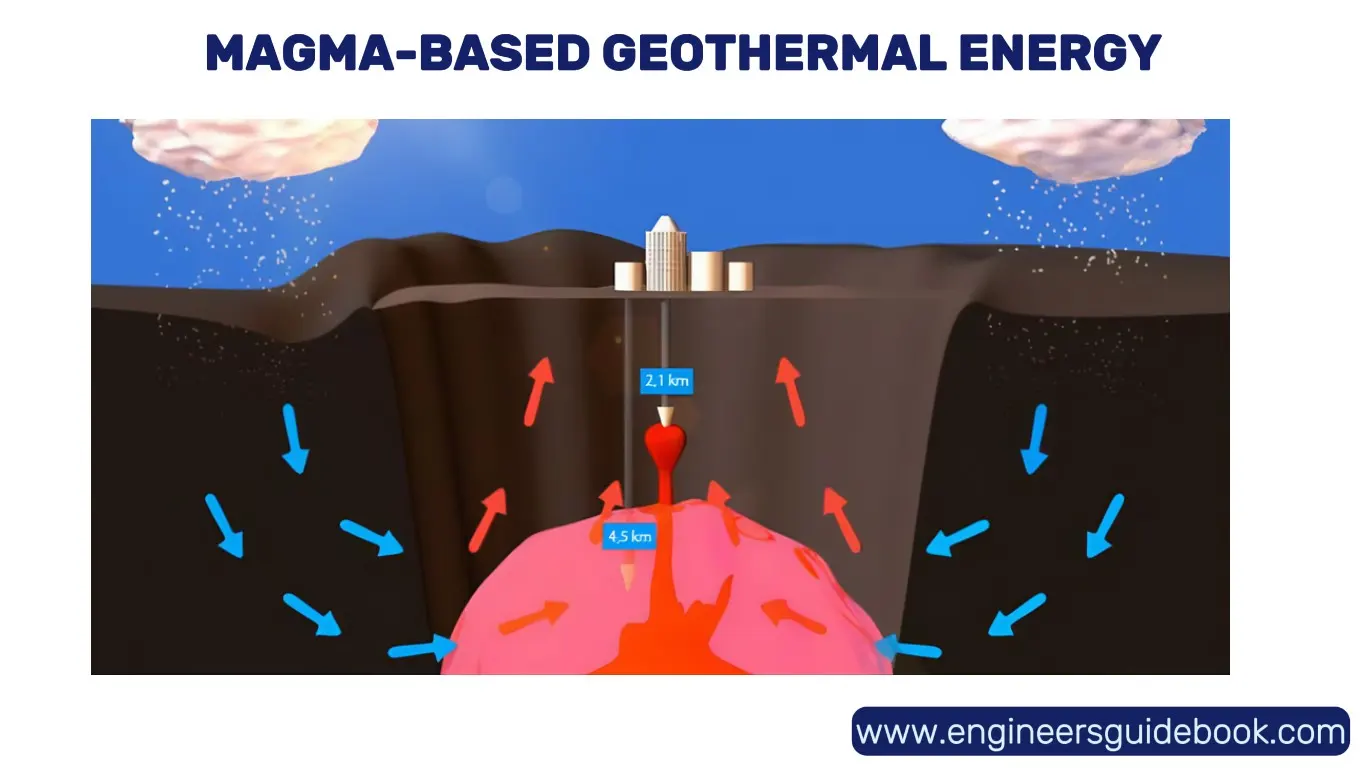

3.3 Magma-Based Geothermal Energy

Magma, the molten rock beneath the Earth’s surface, holds an immense amount of thermal energy. Although technically challenging, advancements in geothermal drilling and heat extraction technologies could unlock this virtually limitless energy source in the future.

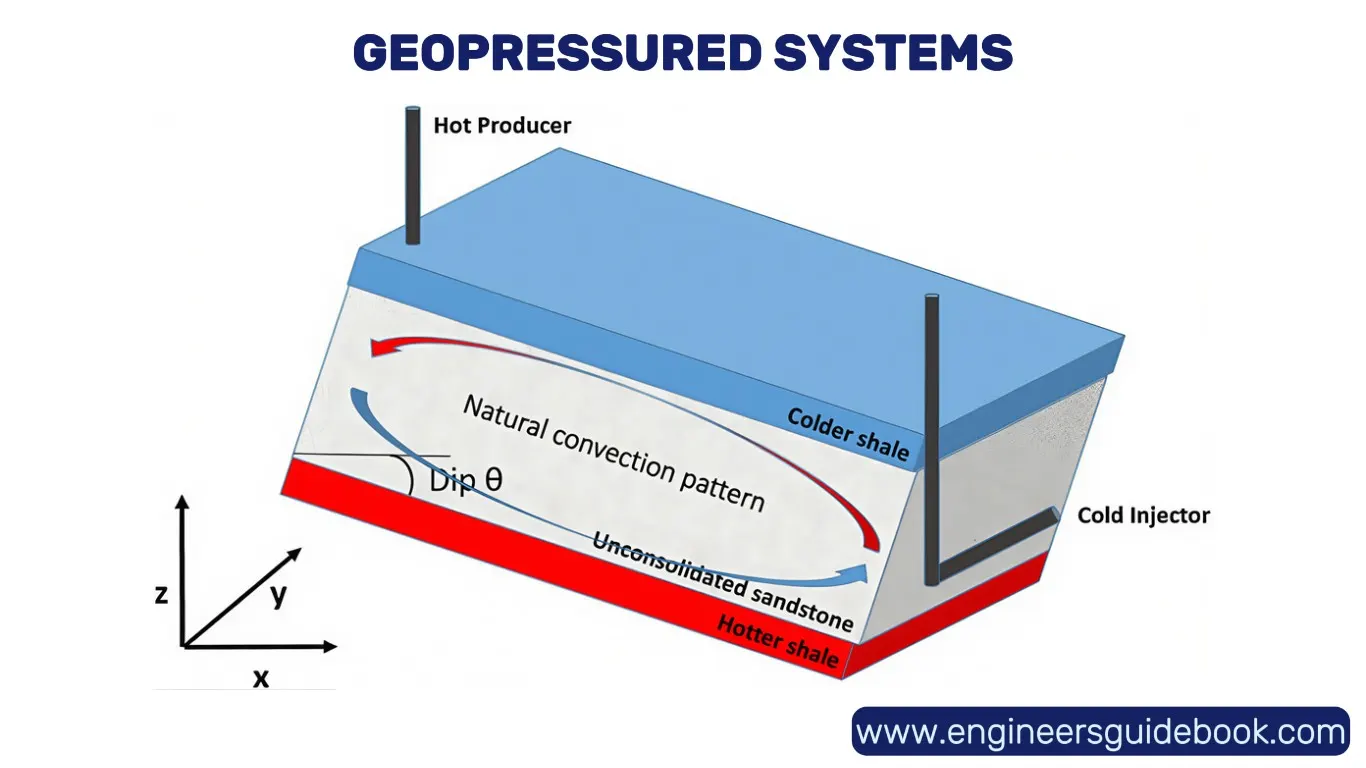

3.4 Geopressured Systems

Geopressured reservoirs contain a combination of hot water, dissolved methane, and high-pressure conditions, offering a dual energy source—thermal and mechanical. These resources remain largely unexplored but hold promise for large-scale energy extraction.

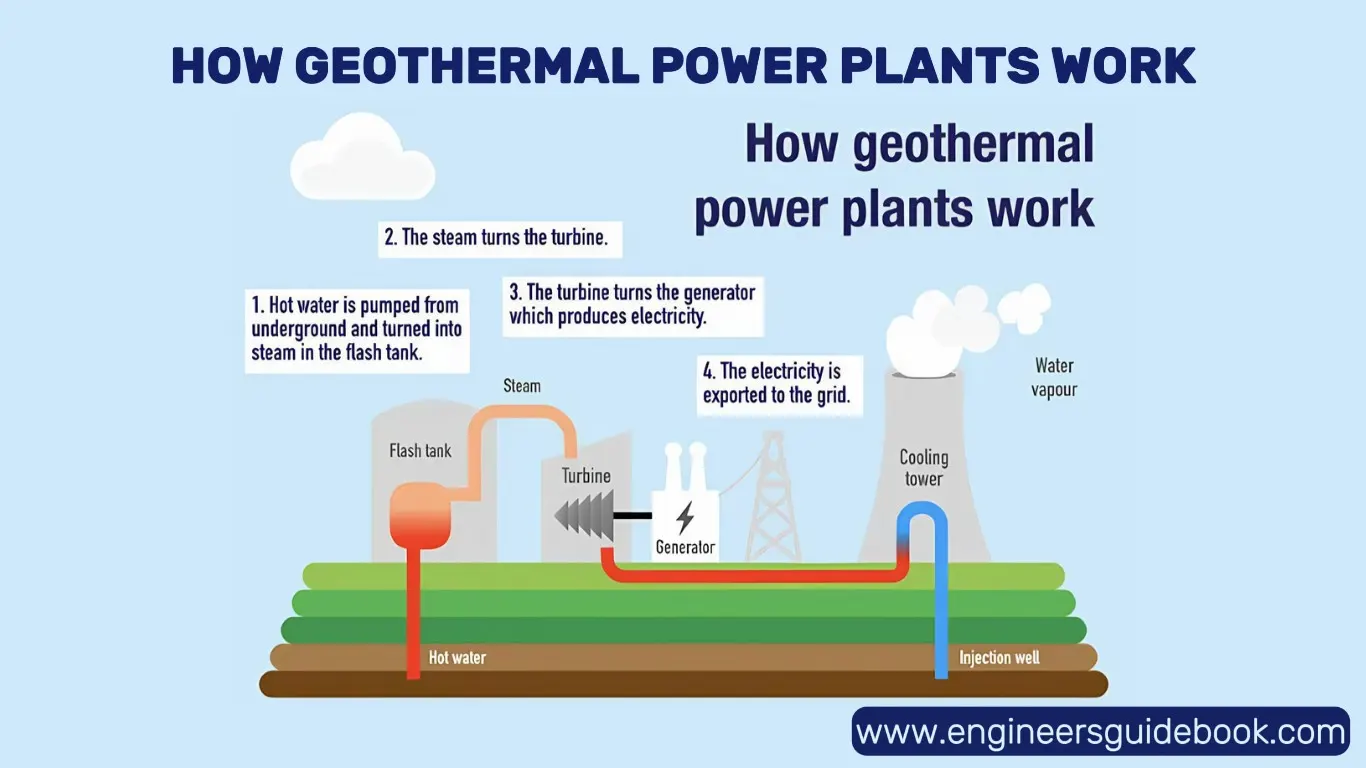

4. How Geothermal Power Plants Work

4.1 Dry Steam Power Plants

Dry steam power plants utilize naturally occurring steam to drive turbines and generate electricity. These plants require high-temperature geothermal fields, making them less widespread but highly efficient.

4.2 Flash Steam Power Plants

Flash steam plants operate by extracting high-pressure hot water from underground reservoirs, which rapidly converts to steam upon pressure reduction. This steam drives turbines to produce electricity before being re-injected into the ground.

4.3 Binary Cycle Power Plants

Binary cycle plants use a secondary working fluid with a lower boiling point than water. Geothermal heat transfers to this fluid, causing it to vaporize and drive turbines. This method enables electricity generation from lower-temperature geothermal sources, enhancing efficiency and resource viability.

4.4 Comparing the Efficiency of Different Geothermal Plant Types

Each geothermal power plant type offers unique advantages and challenges. Dry steam plants provide high efficiency but are limited by resource availability. Flash steam plants are more adaptable, while binary cycle plants expand the potential for geothermal energy utilization in lower-temperature regions.

| Geothermal Plant Type | Efficiency | Resource Availability | Advantages | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry Steam Plants | High | Limited to specific sites | Direct steam usage, high efficiency | Requires high-temperature resources |

| Flash Steam Plants | Moderate to High | More widely available | Adaptable, can utilize moderate to high temp reservoirs | Requires water reinjection to maintain sustainability |

| Binary Cycle Plants | Moderate | Broad availability | Can use lower-temperature resources, environmentally friendly | Slightly lower efficiency compared to dry steam and flash steam |

5. Direct Use Applications of Geothermal Energy

5.1 Space Heating and Cooling

Geothermal heat pumps (GHPs) utilize stable underground temperatures to provide energy-efficient heating and cooling for buildings. By circulating a heat-exchange fluid through underground pipes, GHPs transfer heat to and from the Earth, reducing reliance on conventional HVAC systems.

5.2 Industrial Applications

Industries utilize geothermal energy for diverse applications, including greenhouse heating, food processing, and timber drying. The consistent heat supply enhances efficiency and reduces operational costs, making geothermal an attractive option for energy-intensive industries.

5.3 Geothermal Energy in Spa and Recreational Facilities

Hot springs and geothermal pools have been used for centuries for therapeutic and recreational purposes. Modern spa resorts harness geothermal resources to provide natural, mineral-rich bathing experiences while reducing energy consumption.

5.4 The Role of Geothermal in Desalination and Water Purification

Geothermal heat can be employed in desalination plants to convert seawater into fresh water, addressing global water scarcity issues. By integrating geothermal energy with desalination technologies, sustainable solutions for potable water production can be achieved with minimal environmental impact.

6. Geothermal Energy vs. Other Renewable Energy Sources

6.1 Geothermal vs. Solar Energy: A Battle of Consistency

Solar energy harnesses the sun’s radiation to generate electricity, making it one of the most widely used renewable energy sources. However, its dependency on sunlight renders it intermittent, as energy generation fluctuates with weather conditions and time of day. Geothermal energy, in contrast, offers a consistent and reliable energy supply, unaffected by external climatic variations. While advancements in solar battery storage mitigate some of its intermittency issues, geothermal power remains a more stable baseload energy source. The efficiency of geothermal plants also surpasses solar energy conversion rates, ensuring greater energy output per unit of installed capacity.

6.2 Geothermal vs. Wind Energy: Stability vs. Variability

Wind energy relies on atmospheric air currents to turn turbines, generating electricity. However, wind patterns are unpredictable and can vary dramatically across seasons and geographical locations. Geothermal power, sourced from Earth’s internal heat, provides a steady energy supply with minimal fluctuations. Unlike wind energy, which requires extensive land use and tall turbine structures that can impact bird populations, geothermal installations have a compact footprint. Moreover, wind turbines necessitate substantial maintenance due to mechanical wear, while geothermal plants experience lower operational degradation over time.

6.3 Geothermal vs. Hydropower: Environmental and Geographical Considerations

Hydropower, a dominant renewable energy source, generates electricity through the movement of water in dams and rivers. While highly efficient, its reliance on vast water reservoirs presents significant environmental concerns, including aquatic ecosystem disruption, sedimentation issues, and displacement of local communities. Geothermal energy, on the other hand, has a smaller ecological footprint and does not necessitate altering natural watercourses. Furthermore, geothermal plants can be deployed in diverse landscapes, whereas hydropower projects require specific topographical features, limiting their feasibility.

6.4 Why Geothermal is a Complementary Energy Solution

Rather than competing with other renewables, geothermal energy functions as an ideal complement to solar, wind, and hydropower. Its baseload stability compensates for the intermittency of solar and wind energy, enhancing grid reliability. Additionally, in regions where hydropower may be seasonally affected by droughts, geothermal energy can serve as an auxiliary power source. Integrating geothermal with other renewables creates a more resilient and sustainable energy matrix, reducing reliance on fossil fuels and improving energy security.

7. Environmental Impact of Geothermal Energy

7.1 The Carbon Footprint of Geothermal Power

Geothermal energy produces significantly lower carbon emissions compared to fossil fuels. Binary-cycle geothermal plants, in particular, release near-zero emissions, as they operate in a closed-loop system. Conventional geothermal plants emit minimal amounts of greenhouse gases, primarily from naturally occurring underground reservoirs. However, even these emissions are negligible compared to coal and natural gas power plants, making geothermal a vital contributor to decarbonization efforts.

7.2 Land Use and Habitat Disruption: Myths and Realities

A common misconception is that geothermal energy causes extensive land disturbance. In reality, geothermal power plants require significantly less land per megawatt generated compared to solar and wind farms. While drilling and infrastructure development impact the immediate surroundings, these effects are localized and do not lead to large-scale habitat destruction. In many cases, geothermal sites can be restored post-extraction, preserving environmental integrity.

7.3 Water Consumption and Sustainability Concerns

Geothermal energy requires water for heat extraction and cooling processes. However, binary-cycle geothermal plants utilize closed-loop systems that recycle water, minimizing consumption. Compared to thermoelectric power plants that depend on vast quantities of water for steam generation, geothermal energy is considerably more sustainable. Advanced geothermal technologies continue to improve water efficiency, further mitigating concerns regarding resource depletion.

7.4 Addressing Induced Seismicity and Geological Risks

Induced seismicity, or human-triggered earthquakes, is a potential risk associated with geothermal development. Fluid injection into deep rock formations can occasionally alter subsurface pressures, resulting in minor seismic events. However, proper site selection, rigorous monitoring, and controlled reinjection techniques significantly reduce these risks. Most geothermal plants operate with negligible seismic impact, ensuring long-term geological stability.

8. Economic Viability of Geothermal Energy

8.1 Initial Investment Costs vs. Long-Term Benefits

The upfront capital required for geothermal energy development is substantial, primarily due to exploration and drilling expenses. However, once operational, geothermal plants provide long-term cost advantages through low fuel and maintenance expenses. Their high capacity factor ensures consistent energy output, leading to rapid return on investment and economic sustainability.

8.2 Maintenance and Operational Costs of Geothermal Power Plants

Geothermal power plants require relatively low maintenance compared to fossil fuel and wind energy facilities. The absence of fuel procurement costs and mechanical wear on turbines translates to reduced operational expenditures. Additionally, technological advancements in drilling and plant efficiency further decrease ongoing maintenance requirements, enhancing economic feasibility.

8.3 The Economic Impact on Local Communities

Geothermal energy development stimulates local economies by creating jobs in drilling, construction, and plant operation. Additionally, it provides stable electricity to rural areas, promoting industrial growth and infrastructure development. Many geothermal projects prioritize hiring local workers, fostering long-term economic benefits within host communities.

8.4 Government Incentives and Policies Supporting Geothermal Energy

Several governments worldwide provide tax credits, subsidies, and research funding to promote geothermal energy adoption. Policies such as feed-in tariffs, renewable energy certificates, and grants further incentivize investment in geothermal projects. Supportive regulatory frameworks accelerate industry growth and make geothermal a more attractive energy alternative.

9. Geothermal Energy Around the World

9.1 Leading Countries in Geothermal Energy Production

Countries like the United States, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Iceland lead in geothermal energy production. Their abundant geothermal resources and investment in research have positioned them at the forefront of the industry. Each of these nations leverages geothermal energy for both electricity generation and direct-use applications, showcasing its versatility.

9.2 The Role of Geothermal Energy in Developing Nations

Developing countries with volcanic and tectonic activity have immense geothermal potential. Harnessing this resource provides an opportunity to reduce dependency on imported fossil fuels, improve energy access, and support economic development. Initiatives led by international organizations facilitate geothermal adoption in these regions, fostering energy independence.

9.3 Case Studies: Successful Geothermal Projects Worldwide

Notable projects such as Iceland’s Hellisheidi Power Station and Kenya’s Olkaria Geothermal Plant highlight the effectiveness of geothermal energy. These installations demonstrate high efficiency, sustainability, and significant contributions to national energy grids. Their success underscores the viability of geothermal as a scalable energy solution.

The Future of Geothermal Energy in Global Energy Markets

As nations prioritize clean energy transitions, geothermal power is expected to play an expanding role in global energy portfolios. Enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) and deep-drilling technologies will unlock new resources, increasing geothermal accessibility worldwide. With continued investment, geothermal energy is poised to become a mainstream energy source in the coming decades.

10. Challenges and Limitations of Geothermal Energy

10.1 Geographic Limitations: Why It’s Not Everywhere

Geothermal energy, while abundant in theory, is not uniformly accessible across the globe. Its viability is highly dependent on geological conditions, primarily the presence of tectonic activity or naturally occurring underground heat reservoirs. Regions such as Iceland, the Philippines, and parts of the western United States benefit from significant geothermal resources due to their position along active plate boundaries.

Conversely, in geologically stable areas, heat extraction becomes either technically unfeasible or economically unviable due to the excessive drilling depths required to reach sufficient temperatures. Additionally, the uneven distribution of high-quality geothermal reservoirs limits widespread deployment, necessitating costly exploration and geological surveys to identify potential sites.

10.2 Technical Challenges in Harnessing Deep Geothermal Energy

Exploiting deep geothermal energy presents formidable technical obstacles. Drilling into the Earth’s crust to access high-temperature zones involves withstanding extreme heat and pressure conditions that can degrade equipment over time. Conventional drilling techniques, initially designed for oil and gas extraction, struggle with the abrasiveness of geothermal environments, leading to high operational costs and frequent equipment failures.

Furthermore, managing the reinjection of extracted geothermal fluids to maintain reservoir sustainability is complex, as it requires careful monitoring to prevent mineral scaling, induced seismicity, and pressure imbalances. Overcoming these technical challenges necessitates advancements in high-temperature drilling materials, reservoir management strategies, and improved heat exchange mechanisms to enhance the efficiency and longevity of geothermal systems.

10.3 Public Perception and Acceptance of Geothermal Projects

Despite being a renewable energy source, geothermal projects often encounter public resistance. Concerns over land use, environmental impact, and potential seismic activity contribute to local opposition. Enhanced geothermal systems (EGS), which involve hydraulic stimulation of deep rock formations, have been linked to minor seismic events, raising apprehensions about safety and structural damage in nearby communities. Additionally, the visual and land-use footprint of geothermal plants, particularly in pristine natural areas, can spark environmental debates. Addressing these concerns requires transparent communication, community engagement, and rigorous environmental assessments to ensure that geothermal developments align with societal and ecological expectations.

11. Future Prospects in Geothermal Technology

11.1 Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS): Expanding Usable Resources

EGS represents a groundbreaking approach to expanding geothermal energy access beyond naturally occurring hydrothermal reservoirs. By artificially creating permeability in deep, dry rock formations and injecting water to generate steam, EGS unlocks energy potential in previously untapped regions. This technology significantly broadens the geographic scope of geothermal viability, reducing dependence on specific geological conditions.

11.2 Drilling Innovations: Reducing Costs and Improving Efficiency

Drilling costs constitute a significant portion of geothermal project expenses, often accounting for more than half of the total investment. Innovations in drilling technology, such as laser-assisted drilling, plasma pulse technology, and advanced rotary steerable systems, are transforming the economic feasibility of deep geothermal projects. These advancements reduce wear and tear on equipment, enhance penetration rates, and improve precision in reaching target heat zones.

11.3 Geothermal Energy Storage: A Potential Game-Changer

One of the challenges of renewable energy is ensuring consistent and reliable power generation. Geothermal energy storage, particularly in the form of underground thermal energy storage (UTES), presents a promising solution. By storing excess thermal energy during periods of low demand and retrieving it when needed, geothermal systems can provide a stable and dispatchable energy supply.

12. Conclusion

Geothermal energy stands out as a clean, reliable, and sustainable energy source with significant potential for global energy transition. Its ability to provide constant baseload power, low greenhouse gas emissions, and long-term cost stability makes it a valuable component of the renewable energy mix. Unlike solar and wind, geothermal does not suffer from weather-related intermittency, ensuring a consistent power supply.

As the world shifts towards carbon neutrality, geothermal energy can play a crucial role in decarbonizing electricity generation and direct heating applications. From residential heating networks to industrial processes, geothermal heat utilization offers a pathway to reducing reliance on fossil fuels.

The expansion of geothermal energy requires supportive policies, financial incentives, and strategic investments. Governments and private stakeholders must collaborate to de-risk geothermal projects through favorable regulatory frameworks, research grants, and infrastructure development.

2 Responses

Hi there just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The text in your

article seem to be running off the screen in Ie. I’m not sure if

this is a format issue or something to do with internet browser compatibility but I thought I’d post

to let you know. The layout look great though! Hope you get the issue fixed soon. Many thanks

You are a very smart person!