1. Introduction to Boundary Layer Theory

The study of fluid mechanics encompasses a vast array of phenomena, but among its most pivotal concepts is boundary layer theory. This theory describes the behavior of fluid flow near solid surfaces, explaining how velocity gradients form due to viscous forces. Understanding boundary layers is fundamental to aerodynamics, heat transfer, and numerous engineering applications. The interactions between fluid particles and surfaces dictate the efficiency and stability of vehicles, turbines, and industrial machinery.

2. Historical Background and Development

2.1 The Emergence of Fluid Mechanics

The exploration of fluid behavior has intrigued scientists for centuries. Early civilizations engineered aqueducts and irrigation systems without formal theoretical foundations. However, the scientific study of fluid mechanics began to crystallize in the 18th and 19th centuries with the contributions of luminaries such as Daniel Bernoulli and Leonhard Euler. These pioneers laid the groundwork for understanding fluid motion through principles of energy conservation and pressure distribution.

2.2 Ludwig Prandtl’s Groundbreaking Contribution

The modern conceptualization of boundary layers owes its existence to Ludwig Prandtl, who, in 1904, introduced the revolutionary idea that a thin layer of fluid near a surface governs drag and heat transfer. Prandtl’s insight bridged the gap between theoretical fluid dynamics and practical aerodynamics, enabling advancements in aircraft design and hydrodynamics. His work established a foundation for the mathematical formulation of boundary layer behavior, influencing countless engineering disciplines.

2.3 Evolution of the Boundary Layer Concept

Following Prandtl’s seminal contribution, the study of boundary layers evolved through experimental and computational advancements. Theories on laminar-to-turbulent transition, separation, and reattachment expanded, providing deeper insights into aerodynamics and industrial fluid mechanics. Today, boundary layer theory remains an essential pillar of fluid mechanics, underpinning technological progress in aerospace, automotive engineering, and environmental science.

3. Fundamentals of Fluid Flow

3.1 Viscosity and Its Role in Fluid Motion

Viscosity, the measure of a fluid’s internal resistance to deformation, plays a crucial role in boundary layer formation. Fluids with high viscosity exhibit strong internal friction, resisting flow and creating pronounced velocity gradients. Conversely, low-viscosity fluids experience minimal internal resistance, allowing for smoother flow characteristics. The interaction of viscosity with solid surfaces dictates boundary layer behavior, influencing drag and thermal conductivity.

3.2 Reynolds Number and Flow Regimes

The Reynolds number (Re) serves as a fundamental dimensionless quantity in fluid mechanics, distinguishing between different flow regimes. It is expressed as:

where is fluid density, is velocity, is characteristic length, and is dynamic viscosity. Low Reynolds numbers correspond to laminar flow, characterized by orderly streamlines, while high Reynolds numbers indicate turbulent flow, where chaotic eddies and vortices dominate.

3.3 Differences Between Laminar and Turbulent Flow

Laminar flow exhibits smooth, parallel streamlines with minimal mixing, ensuring predictable velocity distributions. In contrast, turbulent flow involves erratic fluid motion, enhancing mixing but increasing drag. The transition from laminar to turbulent flow depends on factors such as surface roughness, pressure gradients, and flow velocity, significantly impacting engineering designs in aviation, maritime, and industrial processes.

4. Defining the Boundary Layer

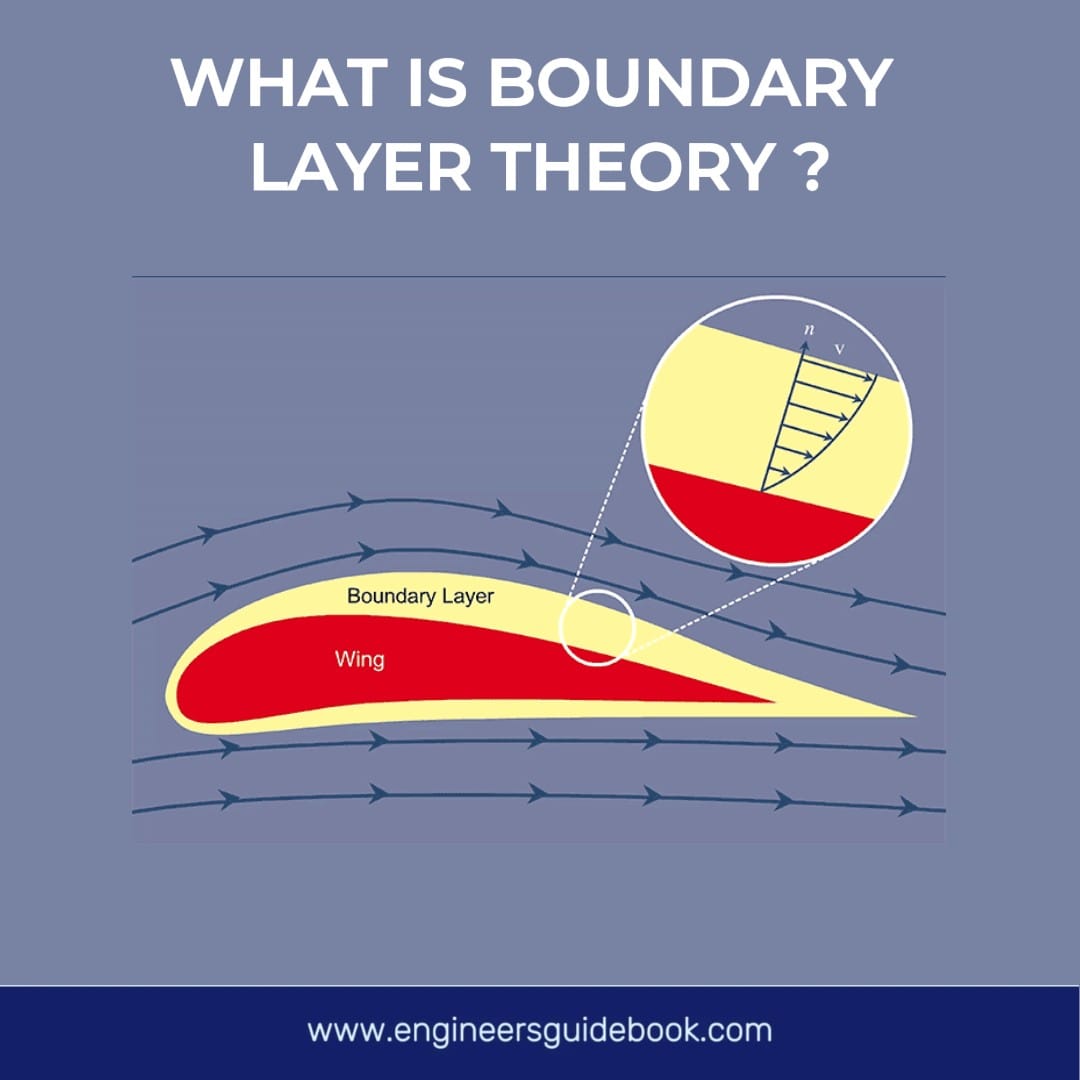

4.1 What Is a Boundary Layer?

A boundary layer is the thin region of fluid adjacent to a solid surface where viscous forces are significant. As fluid flows over a surface, velocity transitions from zero at the wall (due to the no-slip condition) to the free-stream velocity. This region governs drag forces, heat transfer rates, and aerodynamic efficiency.

4.2 The Significance of the No-Slip Condition

The no-slip condition asserts that fluid velocity at a solid boundary equals the boundary’s velocity, implying that stationary surfaces impose a zero-velocity condition on adjacent fluid layers. This results in velocity gradients, leading to shear stress and the development of the boundary layer.

4.3 Boundary Layer Thickness and Its Variations

Boundary layer thickness, denoted as , varies based on flow conditions. A thin boundary layer corresponds to high-velocity gradients and increased shear stress, while a thicker boundary layer suggests lower gradients and reduced interaction with the surface. Factors influencing thickness include viscosity, Reynolds number, and pressure gradients.

5. Classification of Boundary Layers

5.1 Laminar Boundary Layer

In a laminar boundary layer, fluid particles move in well-defined layers without mixing. This results in minimal frictional losses and predictable shear stresses. Laminar flow dominates at low Reynolds numbers and is desirable for applications requiring reduced drag and heat transfer resistance.

5.2 Turbulent Boundary Layer

Turbulent boundary layers exhibit intense mixing, leading to increased momentum transfer and higher shear stresses. While turbulence raises drag, it also enhances heat transfer, making it advantageous in applications such as cooling systems and combustion chambers.

5.3 Transitional Boundary Layer

Between laminar and turbulent states lies the transitional boundary layer, where disturbances amplify before evolving into fully developed turbulence. This transition depends on surface roughness, external disturbances, and Reynolds number, significantly affecting aerodynamic and hydrodynamic performance.

6. Boundary Layer Equations and Assumptions

6.1 Navier-Stokes Equations and Their Simplifications

The Navier-Stokes equations govern fluid motion, encapsulating conservation laws of mass, momentum, and energy. However, their complexity necessitates simplifications for practical boundary layer analysis. The assumption of a thin boundary layer allows for reducing the full equations, facilitating analytical and computational solutions.

6.2 The Prandtl Boundary Layer Equations

Prandtl’s boundary layer equations streamline the Navier-Stokes formulation by assuming that variations in the streamwise direction dominate over variations perpendicular to the surface. These equations enable predictions of velocity profiles, shear stress distributions, and boundary layer separation, essential for aerodynamic and hydrodynamic applications.

6.3 Boundary Layer Approximation

Boundary layer approximations hold valid under conditions where viscous effects are confined to a thin region near the surface. In scenarios involving high Reynolds numbers and negligible pressure gradients, these approximations accurately describe flow behavior, aiding in the design of aircraft wings, marine vessels, and industrial heat exchangers.

7. Velocity Profiles Within the Boundary Layer

7.1 Velocity Gradients

Within the boundary layer, velocity varies from zero at the surface due to the no-slip condition to the free-stream velocity away from the wall. This change in velocity across the thin layer creates a gradient, which influences shear stress and fluid behavior. The nature of these gradients dictates whether the flow remains laminar, transitions to turbulence, or separates from the surface. Understanding velocity gradients is essential for optimizing aerodynamic performance, minimizing drag, and enhancing energy efficiency in fluid systems.

7.2 Velocity Profile in Laminar Flow

In laminar boundary layers, the velocity profile exhibits a smooth, parabolic distribution. The fluid layers move in a well-ordered manner, with lower velocities near the wall and progressively higher velocities away from it. This structured profile results in minimal mixing and lower shear stress. The mathematical representation follows a polynomial relation, with velocity increasing gradually from the wall to the free stream. Laminar profiles are typically observed at lower Reynolds numbers and in scenarios requiring low drag, such as streamlined airfoils and microfluidic devices.

7.3 Velocity Profile in Turbulent Flow

Turbulent boundary layers exhibit a much steeper velocity gradient near the wall and a fuller profile further away. The increased mixing of fluid particles leads to higher shear stresses and greater momentum transfer. Unlike laminar flow, where velocity smoothly increases, turbulent profiles feature random fluctuations and chaotic motion. Despite higher drag forces, turbulent boundary layers resist separation better than their laminar counterparts, making them advantageous in applications requiring sustained attachment, such as aircraft wings and turbine blades.

8. Displacement, Momentum, and Energy Thickness

8.1 Displacement Thickness

Displacement thickness represents the hypothetical shift in the free-stream flow caused by the presence of the boundary layer. As the boundary layer develops, the effective volume available for the external flow decreases, leading to a virtual displacement of streamlines. This parameter is crucial in airfoil and ship hull design, where maintaining an optimal shape ensures minimal flow disruption and reduced drag.

8.2 Momentum Thickness

Momentum thickness quantifies the reduction in momentum flux due to the presence of the boundary layer. It accounts for the velocity deficit within the layer and is instrumental in determining aerodynamic efficiency. A higher momentum thickness indicates greater momentum loss, leading to increased drag forces. Engineers leverage this parameter to assess flow control strategies and improve performance in high-speed transportation and energy systems.

8.3 Energy Thickness

Energy thickness measures the energy deficit within the boundary layer relative to the free-stream velocity. It is particularly relevant in thermal and high-speed applications, where energy dissipation affects overall system performance. A thicker energy layer signifies greater losses, necessitating design modifications to enhance efficiency. Understanding energy thickness aids in optimizing turbine blades, cooling systems, and heat exchangers.

9. Boundary Layer Separation and Its Consequences

9.1 What Causes Boundary Layer Separation?

Boundary layer separation occurs when the flow within the boundary layer loses sufficient momentum to adhere to the surface, causing it to detach. This phenomenon typically arises when adverse pressure gradients decelerate the flow, leading to reverse velocity gradients near the surface. Separation alters the flow field, generating wake regions, turbulence, and increased drag, often resulting in degraded performance in aerodynamic and hydrodynamic applications.

9.2 Adverse Pressure Gradients

An adverse pressure gradient refers to a region where pressure increases in the direction of flow, opposing fluid motion. When this gradient becomes strong enough, it hinders the flow’s ability to maintain momentum, promoting boundary layer separation. This effect is particularly critical in airfoil designs, vehicle aerodynamics, and pipeline systems, where pressure distribution directly influences performance.

9.3 Effects of Flow Separation on Aerodynamic Performance

Flow separation significantly impacts aerodynamic efficiency by creating turbulent wake regions that increase drag and reduce lift. In aircraft, separation leads to stall conditions, compromising control and stability. In industrial applications, such as turbomachinery and automotive design, separation-induced losses diminish overall efficiency. Engineers employ various strategies, including streamlined shaping and flow control devices, to mitigate the adverse effects of separation.

10. Methods to Control Boundary Layer Separation

10.1 Streamlining and Its Effect on Flow

One of the simplest ways to mitigate separation is through streamlining, which involves designing surfaces to maintain smooth flow adherence. Aerodynamically optimized shapes reduce adverse pressure gradients, delaying separation and minimizing drag. Examples include airfoil contours, teardrop-shaped bodies, and hydrodynamic hull designs.

10.2 Suction and Blowing Techniques

Active flow control methods, such as suction and blowing, help manage boundary layer behavior. Suction removes low-momentum fluid from the near-wall region, sustaining attachment, while blowing introduces high-momentum air to re-energize the boundary layer. These techniques are widely used in high-performance aircraft, wind turbines, and cooling systems.

10.3 Vortex Generators and Surface Modifications

Vortex generators are small aerodynamic devices that introduce controlled turbulence to energize the boundary layer, delaying separation. Surface modifications, such as riblets and dimples, reduce drag and enhance flow attachment. These innovations have been successfully implemented in commercial aviation, competitive sports equipment, and energy-efficient vehicles.

11. Boundary Layer Transition Mechanisms

11.1 Natural vs. Forced Transition

Boundary layer transition from laminar to turbulent flow can occur naturally or be externally induced. Natural transition is driven by inherent instabilities in the flow, while forced transition results from external disturbances like rough surfaces or vibrations. Understanding transition mechanisms is crucial for applications where precise control over flow regimes is necessary.

11.2 Influence of Surface Roughness

Surface roughness significantly affects transition behavior by introducing disturbances that accelerate the onset of turbulence. Rough surfaces disrupt the stability of laminar flow, making early transition inevitable. Engineers optimize surface textures to control transition effects, balancing efficiency and performance in various aerodynamic applications.

11.3 Environmental Factors Affecting Transition

External environmental factors, such as temperature variations, pressure fluctuations, and particulate contaminants, influence boundary layer stability. These factors must be accounted for in engineering applications ranging from aircraft performance to wind energy systems.

12. Drag and Its Connection to the Boundary Layer

12.1 Skin Friction Drag: A Direct Result of Viscosity

Skin friction drag arises from the shear stress exerted by viscous forces within the boundary layer. It is predominant in streamlined bodies and plays a vital role in fluid-dynamic efficiency. Minimizing skin friction drag is essential in reducing fuel consumption and improving performance.

12.2 Pressure Drag: A Consequence of Flow Separation

Pressure drag results from the imbalance of pressure forces due to flow separation. Unlike skin friction drag, it dominates in blunt bodies where wake regions develop. Mitigating pressure drag through aerodynamic shaping is fundamental to improving vehicle and aircraft efficiency.

12.3 Strategies for Drag Reduction

Engineers employ various drag reduction techniques, including laminar flow control, active boundary layer manipulation, and innovative surface treatments. These strategies enhance energy efficiency in transportation, aerospace, and industrial processes.

13. Heat Transfer in the Boundary Layer

13.1 The Thermal Boundary Layer Concept

The thermal boundary layer describes temperature variations near a heated or cooled surface, analogous to velocity boundary layers in momentum transfer.

13.2 Convective Heat Transfer and Its Implications

Heat transfer in boundary layers occurs primarily through convection, influencing thermal system efficiency.

13.3 Application in Heat Exchanger Design

Understanding thermal boundary layers aids in optimizing heat exchanger designs, enhancing energy efficiency and performance.

14. Boundary Layer in Aerodynamics and Aircraft Design

Aircraft performance is deeply influenced by the dynamics of the boundary layer. Understanding and manipulating these effects is crucial for optimizing efficiency, stability, and control.

14.1 Lift and Drag: How Boundary Layers Affect Aircraft Performance

Lift and drag are the fundamental aerodynamic forces acting on an aircraft. The boundary layer plays a pivotal role in determining the magnitude of these forces. A well-managed boundary layer ensures smooth airflow over the wings, enhancing lift generation and reducing drag. However, flow separation within the boundary layer can lead to increased pressure drag and reduced aerodynamic efficiency.

14.2 The Role of Wing Design in Boundary Layer Control

The shape and contour of an aircraft’s wing are meticulously designed to control boundary layer behavior. Features such as airfoil camber, leading-edge modifications, and surface smoothness help in maintaining laminar flow for as long as possible before transitioning to turbulence. A well-optimized wing design mitigates flow separation and delays boundary layer detachment, improving overall aircraft performance.

14.3 High-Lift Devices and Boundary Layer Management

High-lift devices, such as slats and flaps, are integral to controlling the boundary layer during takeoff and landing. Slats extend from the leading edge of the wing to energize the airflow, preventing premature separation. Flaps, on the other hand, increase the wing’s effective curvature, enhancing lift generation at lower speeds. These devices ensure that the boundary layer remains attached to the wing surface, enabling safer and more efficient flight operations.

15. Application of Boundary Layer Theory in Engineering

Boundary layer principles extend beyond aerodynamics, influencing a wide array of engineering applications. From naval architecture to automotive design, optimizing boundary layer interactions enhances efficiency and performance.

15.1 Marine Engineering: Effects on Ship Hulls

The boundary layer around a ship’s hull affects hydrodynamic resistance and fuel efficiency. A turbulent boundary layer increases frictional drag, slowing the vessel and consuming more energy. Engineers utilize hull coatings, air lubrication systems, and streamlined designs to minimize these effects, enhancing the ship’s speed and operational economy.

15.2 Automotive Engineering: Streamlining Vehicles for Efficiency

Automobiles rely on aerodynamic refinement to reduce boundary layer-induced drag. Streamlined car bodies, vortex generators, and active aerodynamic components ensure smoother airflow around the vehicle, reducing turbulence and enhancing fuel efficiency. Racing cars, in particular, utilize boundary layer manipulation to maximize downforce while minimizing drag.

15.3 Wind Energy: Optimizing Turbine Blade Performance

Wind turbine blades interact with the boundary layer as they cut through the air, affecting their efficiency. Engineers design blades with optimized airfoil shapes and surface coatings to delay boundary layer separation. Advanced flow control techniques, such as passive vortex generators, help in maximizing energy capture from wind currents.

16. Computational Approaches to Boundary Layer Analysis

With advancements in computational methods, engineers can now model and analyze boundary layer behavior with unprecedented accuracy.

16.1 The Role of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD)

CFD simulations provide a virtual environment to study boundary layer development under varying conditions. These numerical tools help engineers visualize flow separation, pressure distribution, and turbulence patterns, allowing for refined aerodynamic designs.

16.2 Turbulence Modeling Techniques

Accurate turbulence modeling is critical in boundary layer analysis. Approaches such as Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS), Large Eddy Simulation (LES), and Direct Numerical Simulation (DNS) provide varying levels of detail in capturing boundary layer dynamics. Selecting the appropriate model depends on computational resources and required accuracy.

16.3 Experimental Validation of Computational Models

Despite the sophistication of CFD, experimental validation remains essential. Wind tunnel testing, water channel experiments, and field tests ensure that computational predictions align with real-world behavior, bridging the gap between theory and practice.

17. Boundary Layer in Natural Phenomena

Boundary layer effects are not confined to engineered systems; they play a fundamental role in natural environments, influencing weather patterns, ocean currents, and biological functions.

17.1 Atmospheric Boundary Layer: Weather and Climate Effects

The atmospheric boundary layer governs weather conditions near the Earth’s surface. It influences wind patterns, temperature gradients, and pollutant dispersion. Understanding its dynamics is crucial for meteorological forecasting and climate modeling.

17.2 Oceanic Boundary Layers and Their Influence on Marine Currents

In marine environments, the interaction between oceanic boundary layers and wind-driven currents dictates the movement of nutrients, salinity levels, and wave formation. These effects are integral to understanding marine ecosystems and large-scale ocean circulation patterns.

17.3 Boundary Layers in Biological Systems

Even biological systems exhibit boundary layer phenomena. The flow of blood in arteries, the exchange of gases in respiratory systems, and heat dissipation in living organisms all involve boundary layer principles. Studying these effects aids in biomedical advancements and physiological modeling.

18. Experimental Methods for Studying Boundary Layers

Experimental techniques provide valuable insights into boundary layer characteristics, helping validate theoretical models and computational analyses.

18.1 Wind Tunnel Testing and Flow Visualization

Wind tunnel experiments allow researchers to observe boundary layer development under controlled conditions. Techniques such as smoke injection, dye visualization, and pressure measurements help in analyzing airflow behavior.

18.2 Hot-Wire Anemometry and Its Applications

Hot-wire anemometry is a precise method for measuring velocity fluctuations within the boundary layer. This technique is widely used in aerodynamic research to capture fine details of flow instability and transition behavior.

18.3 Laser Doppler Velocimetry for Precise Measurements

Laser Doppler Velocimetry (LDV) offers non-intrusive, high-resolution velocity measurements within the boundary layer. This advanced technique enhances our understanding of turbulence and shear flow characteristics.

19. Challenges and Future Directions in Boundary Layer Research

While significant progress has been made in boundary layer research, challenges remain in achieving a comprehensive understanding of turbulence and flow control.

19.1 Understanding Turbulence

Turbulence remains one of the most complex and least understood phenomena in fluid mechanics. Despite decades of research, predicting and controlling turbulent boundary layers is an ongoing challenge.

19.2 Advances in Supercomputing

With the rise of high-performance computing, more accurate simulations of boundary layer behavior are becoming possible. Supercomputers enable detailed DNS models that capture minute flow structures, paving the way for new insights.

19.3 Emerging Technologies for Boundary Layer Control

Innovative solutions such as plasma actuators, micro-textured surfaces, and active flow control systems are being developed to manage boundary layers more efficiently. These technologies hold promise for revolutionizing aerodynamics, energy efficiency, and fluid engineering.

20. Conclusion

The boundary layer is a fundamental aspect of fluid mechanics, influencing aerodynamics, engineering applications, and natural phenomena. Its study is essential for optimizing performance and efficiency in various domains.

Despite technological advancements, boundary layer theory remains a cornerstone of engineering and scientific research. Its principles continue to guide innovations in aerodynamics, energy efficiency, and fluid control.

The future of boundary layer research lies in advanced computational modeling, experimental breakthroughs, and novel control strategies. As our understanding deepens, new frontiers in aerodynamics and fluid dynamics will emerge, shaping the next generation of engineering innovations.

One Response

are youa phd student. you article clarity is insane and good. very good information that you mentioned in this article. Keep it coming