1. Introduction

1.1 Understanding the Fundamental Forces in Fluid Mechanics

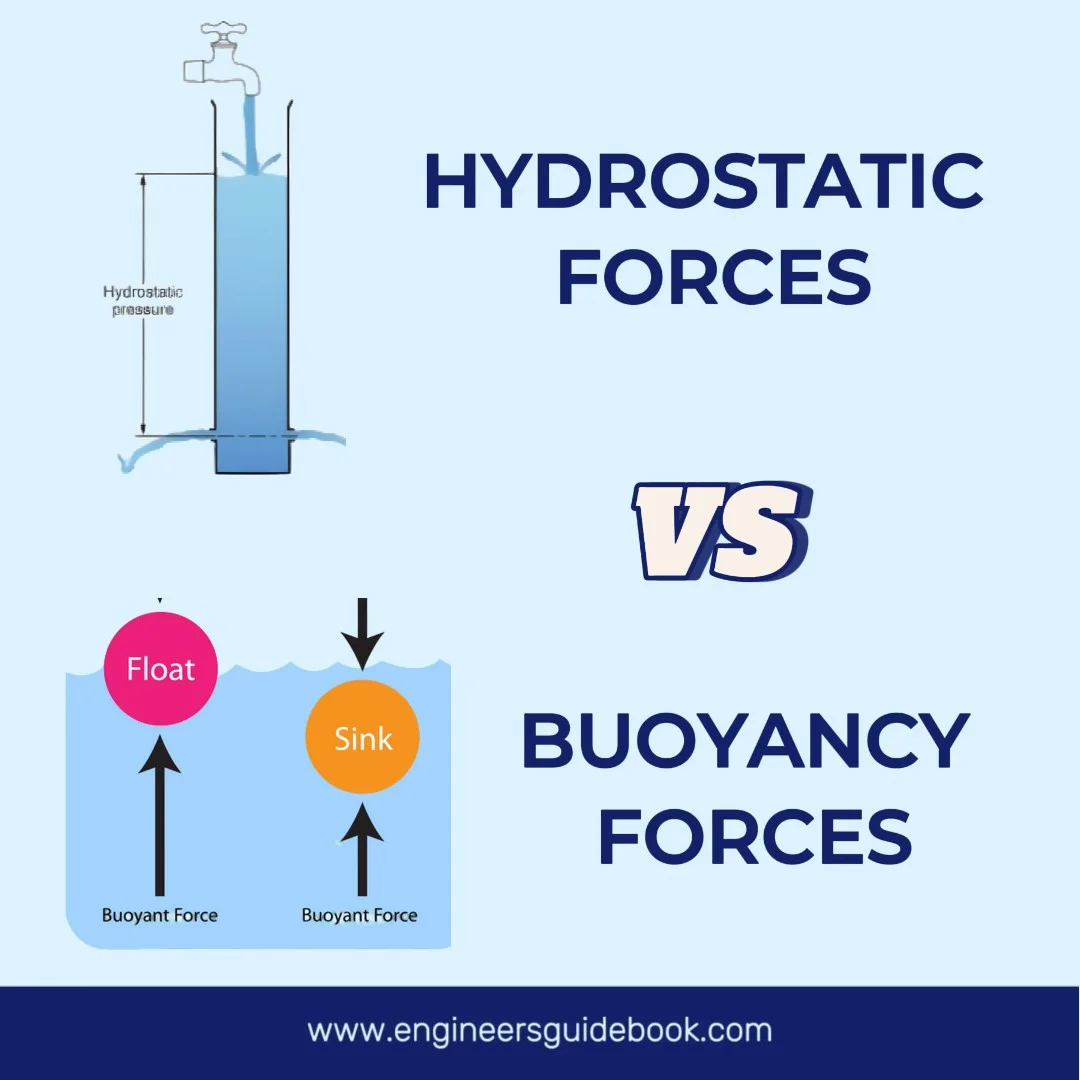

Fluid mechanics is a crucial branch of physics and engineering that governs the behavior of fluids in motion and at rest. Two fundamental forces—hydrostatic and buoyancy forces—play significant roles in understanding how fluids interact with solid bodies. These forces determine whether an object remains submerged, floats, or experiences pressure variations at different depths.

1.2 Importance of Hydrostatic and Buoyancy Forces in Engineering and Science

Hydrostatic and buoyancy forces have vast applications in various scientific and engineering disciplines. These forces influence the structural integrity of underwater constructions, ship design, and even biomedical applications such as blood circulation. Understanding these forces enables engineers to develop stable floating structures, optimize pipeline designs, and improve the efficiency of marine and aerospace technologies.

2. Fundamentals of Fluid Mechanics

2.1 Definition and Properties of Fluids

Fluids, including both liquids and gases, are substances that flow and conform to the shape of their container. They exhibit unique properties such as viscosity, density, and compressibility, which govern their behavior under different conditions.

2.2 Key Principles Governing Fluid Behavior

Fluid mechanics operates under key principles such as Pascal’s Law, Bernoulli’s Principle, and the Continuity Equation. These laws explain how pressure is transmitted in fluids, the relationship between pressure and velocity, and the conservation of mass in fluid flow.

3. Hydrostatic Force

3.1 What is Hydrostatic Force?

Hydrostatic force is the pressure exerted by a fluid at rest. This force acts perpendicularly to the surface of an object submerged in a fluid and increases with depth.

3.2 Mathematical Formulation of Hydrostatic Force

Hydrostatic pressure (P) at a given depth (h) is given by the equation: where:

- is the fluid density,

- is gravitational acceleration,

- is the depth of the fluid.

Hydrostatic force on a submerged surface is calculated as: where is the surface area experiencing pressure.

3.3 Pressure Variation with Depth in a Fluid Column

As depth increases, hydrostatic pressure rises due to the weight of the overlying fluid. This principle explains why deep-sea divers experience higher pressure and why submarine hulls are designed to withstand extreme underwater pressures.

3.4 Applications of Hydrostatic Force in Real-World Scenarios

Hydrostatic force is pivotal in designing hydraulic systems, water supply networks, and large-scale water storage solutions such as dams and reservoirs.

4. Buoyancy Force

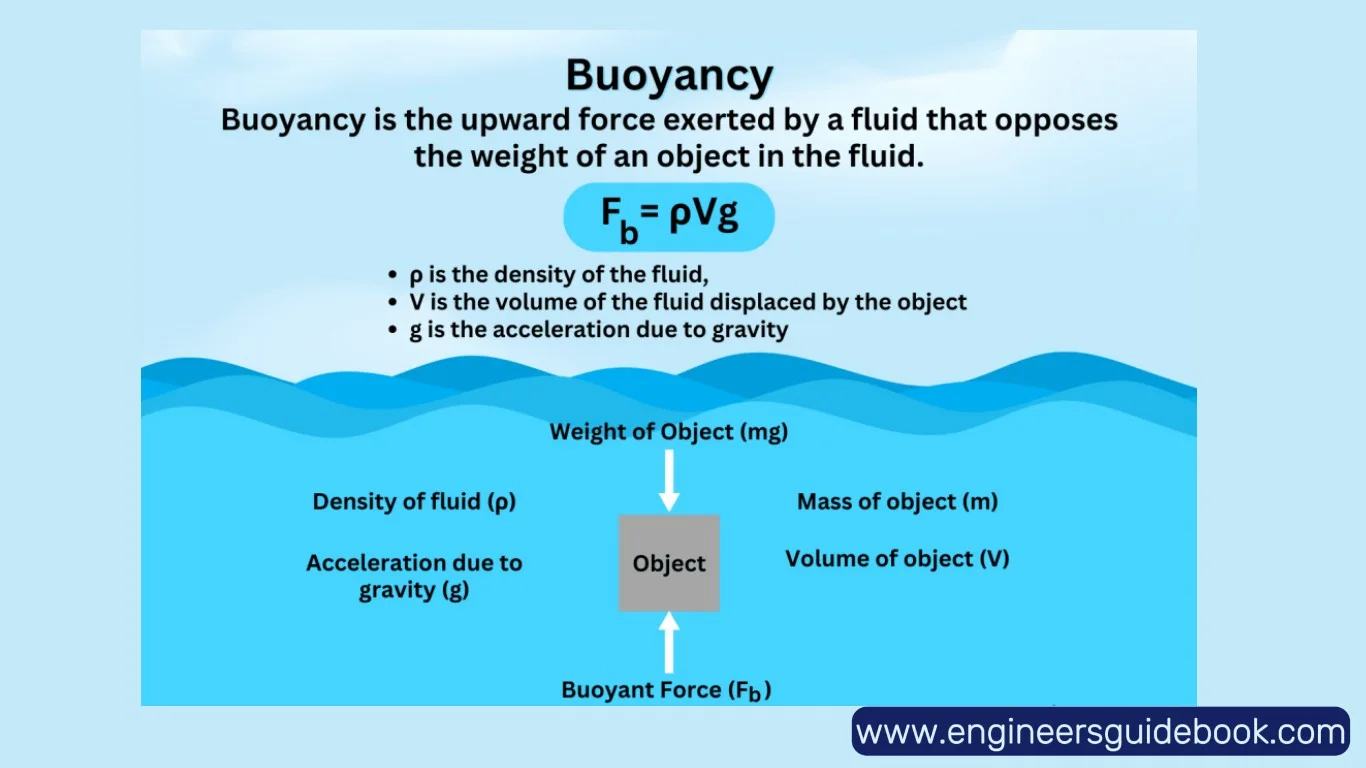

4.1 Defining Buoyancy Force

Buoyancy force is the upward force exerted by a fluid on an object submerged in it. This force counteracts the object’s weight and determines whether it will float, sink, or remain neutrally buoyant.

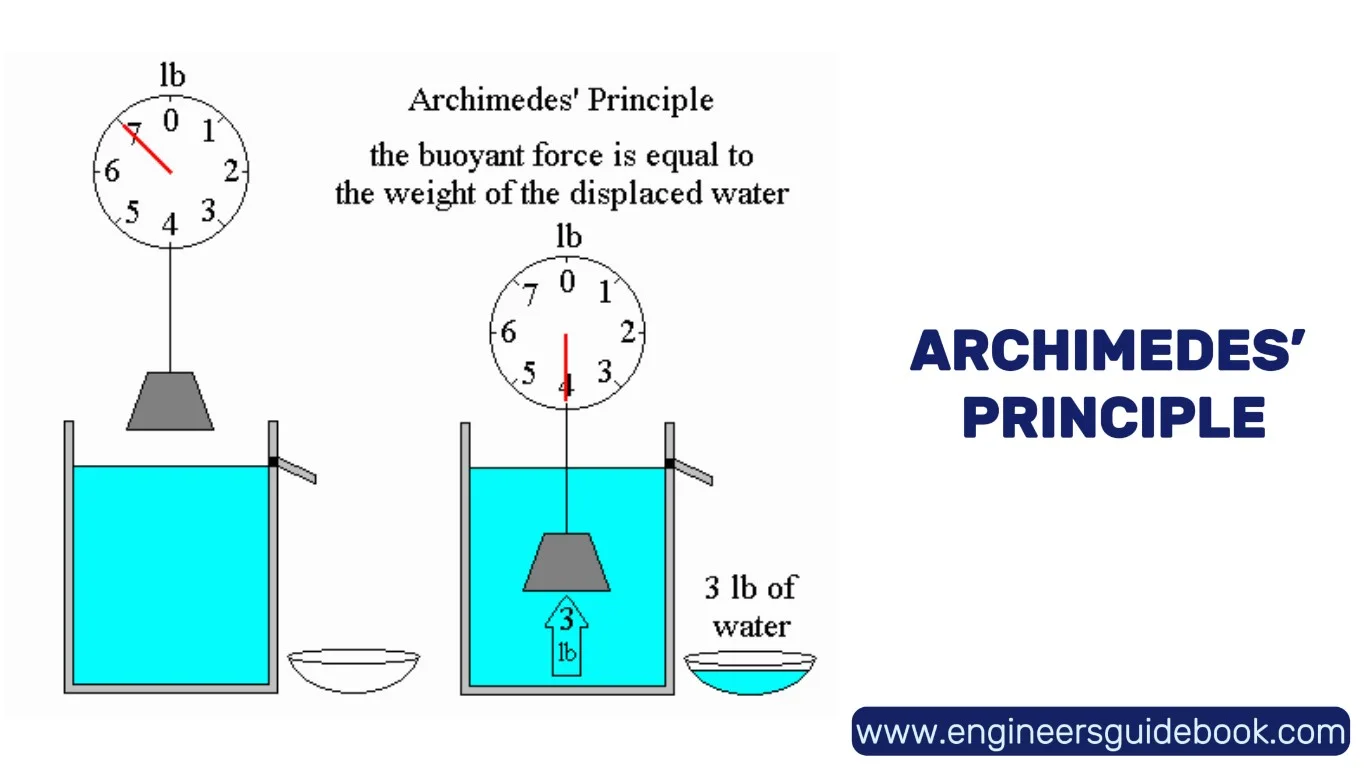

4.2 Archimedes’ Principle and Its Historical Significance

Archimedes’ Principle states that the buoyant force on an object is equal to the weight of the fluid displaced by the object. This principle has been foundational in shipbuilding, submarine engineering, and fluid displacement studies.

4.3 How Buoyancy Force Acts on Submerged and Floating Objects

For an object to float, the buoyant force must balance its weight. If the object’s density is greater than that of the fluid, it sinks; if it is lower, it floats.

5. Key Differences Between Hydrostatic and Buoyancy Forces

| Feature | Hydrostatic Force | Buoyancy Force |

|---|---|---|

| Nature of Force | Acts in all directions on a submerged surface | Acts upwards, opposing gravity |

| Governing Equation | ||

| Dependence | Fluid depth and density | Volume of displaced fluid and fluid density |

| Applications | Hydraulic systems, pressure vessels | Shipbuilding, floating structures |

6. Factors Influencing Hydrostatic Force

6.1 Depth of Fluid and Pressure Distribution

The pressure in a fluid increases with depth due to the weight of the fluid above it. This principle is crucial in engineering applications such as deep-sea exploration, where submarines and underwater structures must withstand immense pressure. Similarly, in dam construction, engineers design the base to be stronger to accommodate higher hydrostatic pressure at greater depths.

6.2 Density of the Fluid and Its Role in Hydrostatic Pressure

The density of a fluid determines how much pressure it exerts at a given depth. Denser fluids, such as mercury, exert more pressure than less dense fluids like water. This factor plays a significant role in the design of underwater equipment, as different fluids require different material strengths to resist pressure. For instance, oil platforms are designed to function in fresh and saltwater, where density variations affect their stability.

6.3 Effects of Gravity on Hydrostatic Pressure

Since gravity is a key factor in hydrostatic pressure (P=ρghP = \rho ghP=ρgh), any changes in gravitational force alter pressure distribution. On planets with lower gravity, like Mars, fluids exert less pressure than they would on Earth. This concept is essential when designing equipment for space exploration or underwater operations in varying gravitational conditions.

7. Factors Affecting Buoyancy Force

7.1 Density of the Displaced Fluid

The buoyant force acting on an object depends on the density of the fluid it displaces. Denser fluids exert a greater buoyant force because they contain more mass per unit volume. This is why objects float more easily in saltwater than in freshwater. Since saltwater has a higher density due to dissolved salts, the same volume of displaced fluid weighs more, increasing the buoyant force and making it easier for objects to remain afloat.

7.2 Volume of the Submerged Object and Its Impact on Buoyancy

The volume of an object submerged in a fluid determines the amount of fluid displaced. According to Archimedes’ Principle, the buoyant force is equal to the weight of the displaced fluid. A larger submerged volume means more fluid is displaced, leading to a greater buoyant force. This is why ships, despite being heavy, float—they are designed with large hulls that displace enough water to generate sufficient buoyant force to counteract their weight.

7.3 How Gravity Influences Buoyant Forces

Buoyancy is directly influenced by gravity because both the buoyant force and the weight of the object depend on gravitational acceleration (g). In environments with stronger gravity, such as Jupiter, the weight of objects increases, but the buoyant force remains proportional to the displaced fluid’s weight.

This means objects are less likely to float. Conversely, in weaker gravity environments like the Moon, objects experience reduced weight, and buoyancy effects are diminished since fluids behave differently under low gravity.

8. Hydrostatic Force in Practical Applications

8.1 Design of Dams and Reservoirs

Dams are massive structures built to hold back and control water. One of the primary engineering challenges in dam construction is dealing with hydrostatic pressure, which is the force exerted by the water on the dam’s surface.

As the depth of water increases, the pressure also increases, requiring the dam to be reinforced, especially at its base. To prevent structural failure, dams are designed with thick bases, strong materials (such as concrete and reinforced steel), and features like spillways to release excess water safely.

8.2 Pressure Considerations in Underwater Tunnels and Pipelines

Underwater tunnels and pipelines are subjected to immense external hydrostatic pressure, especially when placed deep underwater. Engineers must ensure these structures can withstand this pressure to avoid collapse or deformation. The design considerations include:

Anchoring and buoyancy control: Pipelines need to be secured properly to prevent unwanted movement due to buoyancy forces.

Material selection: Strong and flexible materials like reinforced steel or composite materials are used to handle external pressure.

Wall thickness: The deeper the tunnel or pipeline, the thicker the walls must be to withstand the pressure.

8.3 Engineering Challenges in High-Pressure Fluid Environments

In deep-sea environments, submarines and remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) face extreme hydrostatic pressure that can exceed several hundred atmospheres. To withstand these conditions:

Internal pressurization and ballast systems allow submarines to adjust their depth without being crushed by the surrounding water pressure.

Specialized materials like titanium and advanced composites are used to prevent structural failure.

Pressure-resistant hulls with spherical or cylindrical shapes help distribute the pressure evenly.

9. Buoyancy in Real-World Engineering Applications

9.1 Ship Design and Stability

Ships are designed with carefully calculated buoyancy to ensure they remain stable in water. Naval architects optimize the hull shape and weight distribution to maintain equilibrium under different loading conditions. The ship’s center of gravity and center of buoyancy must be balanced to prevent excessive tilting or capsizing. This principle is critical in cargo ships, cruise liners, and naval vessels.

9.2 Submarine Ballast Systems

Submarines use ballast tanks to control their depth in water. These tanks can be filled with water to increase the submarine’s weight and allow it to submerge. To resurface, compressed air is used to force the water out of the tanks, making the submarine lighter and increasing buoyancy. This controlled buoyancy adjustment enables submarines to navigate efficiently under different sea conditions.

9.3 Floating Bridges and Offshore Structures

Floating bridges and offshore platforms, such as oil rigs, rely on buoyancy to remain stable despite changing water levels and environmental factors like waves and currents. These structures are designed with buoyant pontoons or large air-filled compartments that provide lift and stability. Engineers carefully calculate weight distribution to prevent excessive tilting and ensure long-term durability in harsh marine environments.

10. Conclusion

Understanding the differences between hydrostatic and buoyancy forces is essential in designing efficient structures, from ships and submarines to hydraulic systems and reservoirs. By leveraging these fundamental fluid mechanics principles, engineers can develop innovative solutions for both terrestrial and marine environments.

FAQ’s

What is hydrostatic force?

Hydrostatic force is the pressure exerted by a fluid at rest on a submerged surface, increasing with depth.

What is buoyancy force?

Buoyancy force is the upward force exerted by a fluid on an object, counteracting its weight and determining whether it floats or sinks.

How is hydrostatic pressure calculated?

It is given by P=ρgh, where ρ\rhoρ is the fluid density, g is gravity, and h is depth.

What is Archimedes’ Principle?

It states that the buoyant force on an object equals the weight of the displaced fluid.

Why do objects float or sink?

Objects float if their density is less than the fluid’s density and sink if it is greater.

How does hydrostatic force affect dam design?

Dams are built with thick bases to withstand increasing pressure at greater depths.

Why do submarines use ballast tanks?

Ballast tanks control buoyancy by adjusting the amount of water inside, allowing submarines to submerge or surface.

How does fluid density affect buoyancy?

A denser fluid exerts a greater buoyant force, making floating easier in saltwater than freshwater.

One Response

Great breakdown of a confusing topic. The clear comparison between hydrostatic and buoyancy forces is so helpful!